In The Power of Peers: How the Company You Keep Drives Leadership Growth & Success, we outline four ways we typically engage others. We connect, network, optimize and accelerate. We defined optimize in terms of what happens when peers work together toward a common goal – when they chase perfection in the pursuit of excellence. During my recent trip to Washington, DC and the National Gallery of Art, I never thought I’d discover one of the most remarkable examples of optimizing I could have ever imagined.

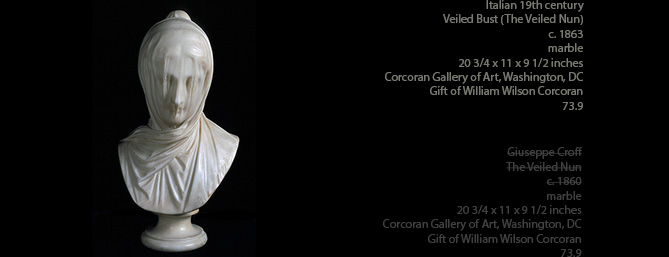

The sculpture pictured above is commonly referred to as “The Veiled Nun.” Until I got close enough to realize otherwise, it looks as if an actual veil is draped over the marble statute. It’s absolutely breathtaking. I immediately looked for the plaque that I assumed would identify who sculpted this masterpiece and it read, “Italian.” How could this be? How could no one know who crafted this masterful work? So I thought I’d look into it when I returned home. Turns out, the story behind “The Veiled Nun” is every bit as amazing as the piece itself.

Purchased in March 1863 in Rome by William Wilson Corcoran [1798-1888], it was gifted to the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1873, and later acquired by the National Gallery of Art (2014). Until recently, it was assumed that it was the work of Giuseppe Croff. Experts have since concurred that it was actually created in a commercial workshop in Rome, making it unlikely we will ever know the name of the carver(s). Here’s where it gets interesting, as Lisa Strong, then Manager of Curatorial Affairs at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, tells the story:

It is a little known fact that sculpture in this period was produced by a designer (the artist who signs the piece) and a craftsman who actually carved the piece in marble. The artist would have designed the sculpture in plaster or wax and then submitted that model to the workshop for production. Studio labor was specialized, so there would have been one craftsman to select and rough out the block of marble and to confirm there were no flaws in the stone. Next, another craftsman used a mechanism called a pointing device to drill into the block and match the contours of the plaster model. Yet another craftsman carved the face, followed by specialists in hair, eyes, etc. and a final artisan who polished the surface. This commercial production system was the same whether a workshop was producing a signed piece of sculpture under an artist’s supervision or a copy of an antique or eighteenth century design.

Strong goes on to say:

Once Corcoran returned to Washington, D.C. and put The Veiled Nun on display in his home, it received only an occasional mention from visitors. Likewise, its exhibition in the first Corcoran building (now the Renwick) in a niche of the rotunda, elicited little comment. This is perhaps because The Veiled Nun would have been a fairly familiar subject for Victorian audiences who were accustomed to virtuoso sculptural techniques. It was only in the early twentieth century, long after the taste for realistic sculpture had changed and the market for veiled busts had evaporated that the public began to take note. By 1969, when Readers Digest approached the Corcoran with a request for its audience’s favorite piece, The Veiled Nun was an easy answer. It was firmly entrenched as the one of Washington’s most beloved artworks and it remains among its most popular today.

As it should. I’ll never forget the first moment I saw it or the story of how it was crafted. It has raised the bar for me forever when it comes to what a group of peers, committed to a common goal, is capable of achieving. The people who created “The Veiled Nun” didn’t just chase perfection, they caught it. I share this story with you, so you can share it with your team. Enjoy! (Be sure to see it for yourself during your next visit to our nation’s capital).